Pictured above: Parish Church of Our Lady of the Rosary commands one block of buildings lining Plaza Mayor.

It’s a vast space!

I stand at the northwest corner of cobblestoned Plaza Mayor, central square of magical Villa de Leyva, Colombia, population 17,000 inhabitants. Plaza Mayor measures a third of an acre. It’s empty, except for a small sixteenth century mudejar-style fountain in its center. Also, as if to elevate its noble purpose, a heart-shaped wire mesh recycling bin for bottles and cans sits off towards one corner. One and two-story colonial buildings line the square’s four sides, housing city offices, boutique hotels, shops, cafes, and bars and the impressive seventeenth century Parish Church of Our Lady of the Rosary.

Plaza Mayor holds the record as the largest town square in Colombia (larger than Plaza Bolivar in capital city Bogotá). The Spanish army used the square a few centuries ago to execute military drills and to execute local rebels who fought for independence.

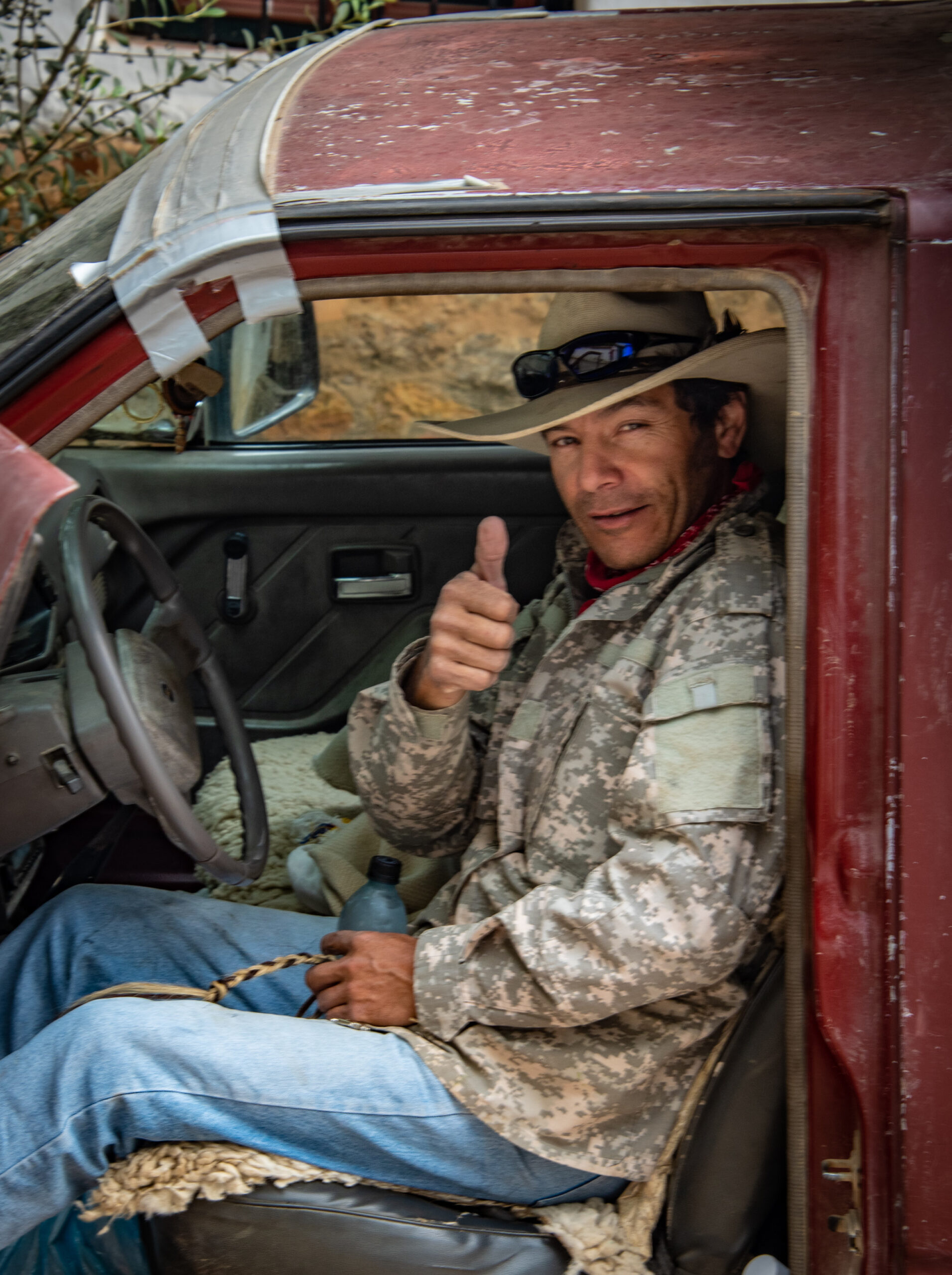

Getting to Villa de Leyva: The Pan-American Highway

Villa de Leyva sits in a semi-arid valley of the Eastern Andes Mountains at 7000 feet, a pleasant three-hour drive traveling north from Bogotá on the Pan-American Highway, with Juan behind the wheel of our late model Renault SUV and our guide Tomás Vargas. Rolling hills frame the road on either side, quilted with lush green fields for growing crops and grazing animals.

I imagine they must be very old mountains to be so gentle in appearance. “Sediment deposits cover them. That’s why they’re so fertile,” says Tomás. His comment confuses me. Sediment? Later in our visit, I learn why that’s true.

We stop at a roadside pastry and sandwich shop to stretch and snack on arepas (“super thick Mexican corn tortillas”) and fresh papaya juice, before reaching Puenta de Boyacá (Boyacá Bridge). A national monument and memorial to Colombian independence, the small rebuilt bridge crossing the narrow Teatinos River appears insignificant; yet the most significant battle for freedom from Spain took place here. With a touch of reverence in his voice, Tomás tells us its story.

On August 7, 1819, 3000 freedom fighters, led by South American liberator Simón Bolivar and Colombian hero Francisco de Paula Santander defeated the Spanish army at this bridge on its way to retake Bogotá, essentially freeing from Spanish rule what was then known as New Granada (now the countries of Colombia, Panama, Ecuador, and Venezuela). Impressive bronze monuments of these heroes and high-flying flags of these countries adorn the handsomely maintained battlefield.

As a native Philadelphian, I liken Puenta de Boyacá with the importance of Independence National Historical Park and the Liberty Bell to Americans as symbols of our own freedom from foreign rule, just 43 years earlier.

Retail shops, boutique hotels, bars and restaurants operate from traditional buildings and store fronts along the town’s small handsome commercial district.

A postcard town comes to life

Except for the presence of automobiles, I feel like I’ve arrived in the past. Villa de Leyva’s charm lies in its authenticity of a sixteenth century Spanish colonial village. It seems not much has changed in appearance over the last several centuries since André Diaz Venero de Leyva founded the town in 1572. Its uniform architecture exhibits typical colonial style with traces of Moorish influence from southern Spain.

Balconies and bay windows embellish many of the all-white stuccoed houses, and along with doors and trim, appear in black, brown, or dark green paint. Huge cobblestones pave streets, most without sidewalks except near Plaza Mayor. I carefully watch where I step. Red terracotta-tiled roofs cap structures, completing the town’s visual allure. These days, any new or rehabbed construction must conform to strict guidelines for building materials and architectural style and details.

Located a few blocks from the plaza, Casa Terra, our home for two nights, reminds me of typical Spanish houses where an unassuming solid wall punctuated with an entrance defines its street presence. A wooden façade, in which a door is cut, now fills 10-room Casa Terra’s large stone arch, probably a former entrance for carriages and horses.

I ring the bell, the lock buzzes, and we enter the life of the compound. Open grounds landscaped with cacti and flowering trees hold five one- and two-story buildings that house ten guest rooms, offices, meeting room, and kitchen for cooking delicious breakfasts served in the inn’s courtyard.

Villa de Leyva attracts tourists, of course, mostly Colombians since the town ranks as one of the prettiest in the country. Visitors discover its main attraction by wandering its quaint streets to poke into handicraft and clothing stores, cafes, boutique hotels, and bars. Marquees, neon signs, brightly painted facades I gratefully don’t see.

Teachers lead a busload of well-behaved middle school children from Bogotá who want to chat. One teacher nicely asks me not to take pictures of the children. In the attractive main two-block commercial area, the town prohibits cars and the streetscape sports attractive colonial-style lighting., perfect for strolling. Near our Casa, a well-maintained half-block green park offers benches to rest among the cool trees.

Museo El Fósil - This can’t be a real fossil!

Tomás and I take off in the Renault to visit a few note-worthy sites outside of town. Among them, the eye-opener––two-room Museo El Fósil, housing the nearly complete skeleton of Monquirasaurus boyacensis, a 24-foot-long aquatic animal and relative of the crocodile, found by farmers in 1977. Aquatic?! Here, 7000 feet above sea level?! Instead of trying to move it, the government built the museum around it.

A little Googling reveals that the ocean once covered most of Colombia, even the Andean foothills, 115 million years ago, when “Miss M” (experts determined she’s a juvenile; I assigned her gender) swam in twenty feet of water. So that’s what Tomás referred to when he said the hills were covered with sediment. The skeleton’s hind flipper and tail are missing, and archeologists posit that this water-bound leviathan accidentally beached herself in shallow water. Other predators tore pieces from her body for supper.

Museo El Fósil contains thousands of mollusk shells embedded in rock, and a prehistoric dolphin completes its small, impactful collection. The museum teaches me a life lesson. It reminds me I’m just a “mote in God’s eye” (the title of a 1974 science fiction novel that describes humanity’s insignificance relative to space and time).

Fossils litter the entire Villa de Leyva region. A local monastery, Convento del Santo Ecce Homo, uses fossils embedded in cement to adorn its courtyard’s walls. Now I see fossils everywhere in the village, in the streets, on walls, and as motifs on tee-shirts and dresses for sale.

Where to Eat in Villa De Leyva - Wining and Dining

We wrap up our two-day visit with the second of two delicious dinners at local restaurants. Yesterday, at Mercado Municipal, we entered through what appeared to be part of the kitchen, and the staff led us outside to a lushly green open-air courtyard table for two tasty barbecue dinners–one lamb and the other, pork. At La Maria Bistro, where a wall mural of the restaurant’s founder presides over the dining room, I devour my first of several whole crispy fried fish I enjoy during this South American adventure, this time a sea bass.

Colombia’s wine production, traditionally negligible, is developing and improving its quality rapidly. The high-altitude climate and semi-arid growing conditions in this region provide one of the best opportunities to create top quality Colombian wines. We discover a few tasty varieties at Vinedo Ain Karim, a local winery, which we tour with a busload of bicyclists of all ages from Europe, South America, and the U.S., (their wheels are stored on the bus) traversing Colombia’s mountainous terrain. The winery’s sauvignon blanc and a pinot noir proves quite tasty. Mostly, though, we find excellent Chilean and Argentinian wines on menus as we travel the country.

It’s our last night and I want to experience Plaza Mayor at dusk. A few people crisscross the square as twilight settles. I hear children laughing across the emptiness. Lights from buildings and the church glow as night falls, and the enormous void of the square darkens. Magic fills the vast space.

How to Get to Villa De LEYVA

By Plane non-stop to Bogotá: Several daily flights from Miami; JFK (New York) has a few daily flights. Also, less frequent flights from 10 other U.S. cities.

By Bus non-stop from Bogotá: Expreso Gaviata or Valle de Tenza bus lines. From Terminal Salitre or Terminal del Norte (most convenient). Around $12. Three hours.

- By Taxi or Uber: $35-$50. Three hours

Travel Companies

- Travel Agency: kimkim––Online travel agency, www.kimkim.com. I used Kimkim for both Colombia and Portugal trips. They connected us to local travel experts.

- Local Agency: Aracanto Colombian Travel Specialists, www.aracanto.com

Felipe Rico and his team provided extraordinary service, arranging hotels, transportation, excellent local guides, and often dinner reservations. They kept in touch with us every day throughout the trip.